May 1, 2002

The Potential Convergence of the D&O Policy

THE POTENTIAL CONVERGENCE OF THE D&O POLICY AND THE GENERAL LIABILITY POLICY TO CONCURRENTLY COVER PROPERTY DAMAGE

R. Scott Brearley

May 2002

THE POTENTIAL CONVERGENCE OF THE D&O POLICY AND THE GENERAL LIABILITY POLICY TO CONCURRENTLY AFFORD COVERAGE FOR DAMAGE TO PROPERTY

I. INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, to consider whether coverage for property damage claims is found solely in general liability policies or whether a D&O policy could possibly afford that coverage. D&O policies typically exclude claims for “bodily injury or property damage” and conventional wisdom would relegate those same claims to the general liability carrier. The question to be considered is whether there are cases where coverage is potentially afforded by both the general liability policy and the D&O policy or whether these policies, as they relate to “’property damage”, are mutually exclusive. Secondly, a synopsis is provided of the leading cases delineating the line between claims for pure economic loss and claims for property damage.

II. D&O POLICY EXCLUSIONS FOR “PROPERTY DAMAGE”

The following wordings are representative of exclusions for “property damage” in Canadian D&O policies:

1. The insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for loss in connection with any claim …

(x) for any actual or alleged property damage, or any actual or alleged damage to or destruction of any tangible property including loss of use thereof.

2. The Insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for loss in connection with any Claim made against the Insured:

(x) for bodily injury, sickness, disease, death or emotional distress of any person, or damage to or destruction of any tangible property including loss of use thereof;

3. The Insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for loss in connection with any claim made against the Insured Persons:

…

x. based upon, arising out of, relating to, in consequence of, or in any way involving, … damage to or destruction of any tangible property, including loss of use thereof.

4. This insurance does not apply to:

(x) Claims arising out of or attributable to … damage to or destruction of any tangible property including loss of use thereof … . However, this exclusion shall not apply to any Claim made directly or derivatively by a security holder of the Corporation in his/her right as such provided that such Claim is brought totally without the solicitation, assistance, participation or intervention of any Insured(s) or the Corporation.

These examples all have in common an exclusion for loss of use, a concern for tangible property and that property’s damage or destruction. The fourth exclusion is obviously different since the wording admits of an exception for direct or derivative actions advanced by shareholders. The third example is worded to achieve a greater degree of exclusion. That is, the exclusion is potentially wider in scope by excluding claims in any way involving property damage.

Conversely, commercial general liability policies grant coverage for damages attributable to an insured for property damage. The wording for this traditional grant of coverage has proven troublesome for the insurer. A brief overview of the history and judicial treatment of the wordings is useful in understanding the potential interplay between CGL and D&O policies.

III. CGL POLICIES AND PROPERTY DAMAGE – A HISTORY

The definition for “Property Damage” has undergone significant amendment over its history. Four differing definitions have been in common use since the 1950’s. Insurers have tended to adopt language which has varied either marginally or significantly from the four standard definitions. These four definitions – outlined here chronologically – become successively narrower in their respective scopes of coverage as insurers became motivated to overcome generous judicial interpretations.

A. PRE-1966 DEFINITIONS

Prior to 1966, general liability policies did not contain a separate definition of the term “property damage”. Terminology was typically set out in the insuring Agreement itself. The policy provided for coverage for “injury to or destruction of property”. Judicial interpretation of this phrase led to a later revision, which defined the term “property damage” to mean “injury to or destruction of tangible property”. The word “tangible” was added to seemingly overcome cases which concluded that coverage was available for loss to intangible property, such as goodwill or profits. However, dissatisfaction with the interpretation of this phrase did not end.

Prior to 1966, the undefined nature of the term “property damage” led Courts to give the term its common, popular and ordinary meaning. Since the phrase was capable of more than one reasonable meaning, ambiguity in the phrase was judicially resolved in favour of the insured. The term “injury” was given a broad interpretation and was construed to include both physical and non-physical harm or damage. In U.S. Fidelity & Guaranty Co. v. Mayor’s Jewelers of Pompano Inc., “injury” was interpreted as encompassing any wrong or damage, including non-physical damage. In Yakima Cement Products Co. v. Great American Insurance Co., the term “injury” was interpreted to mean both physical and non-physical harm.

Similarly, in Canada, the term “injury” was interpreted broadly in the case of Hildon Hotel (1963) Ltd. v. Dominion Insurance Corp. Oil had leaked from the insured’s storage tank into a harbour. A government authority had obtained judgement for the cost of the cleanup. The insurer denied indemnity on the basis that the mere presence of oil in the harbour did not amount to property damage.

The insuring agreement required indemnity where damages arose “because of injury to or destruction of property”. The Court concluded that the terms “injury” and “damage” were distinct. “Injury” was interpreted to encompass an infringement of property and was broader than the term “damage”. On the facts, the Court found an “injury”.

The judicial treatment of the term “injury” as broader than the term “damage” is common to both the U.S. and Canada. “Injury” can include physical interference with property but extends to include non-physical infringement or interference. The term “property”, because it was undefined, was also interpreted broadly to include both intangible and tangible property.

B. 1966 DEFINITION

The 1966 general liability wording provided that an insurer would indemnify for damages resulting from “property damage”, which was defined to mean “injury to or destruction of tangible property”. The insertion of the word ‘tangible’ was intended to eliminate coverage for intangible property loss. In Massey v. Decca Drilling Co., an insured sought a defense under its general liability policies when an action was commenced for the loss of mineral rights. The Court concluded that a loss of intangible rights did not fall within coverage.

Once physical harm or loss of use of tangible property has occurred, however, all resulting damage, including pure economic loss is covered. In General Insurance Co. of America v. Gauger, an insured was sued by farmers for a reduced yield when the wrong seed was supplied. The insurer took the position that the lawsuit was one for lost profits involving intangible property. The Court disagreed, stating that the reduction in yield was evidence of injury to the crops; a tangible property. The loss of profits was simply the appropriate measure of damages.

C. 1973 DEFINITION

The 1973 amendment to the general liability policy defined property damage as:

1. physical injury to or destruction of tangible property which occurs during the policy period, including the loss of use thereof at any time resulting therefrom, or;

2. loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed provided such loss of use is caused by an occurrence during the policy period.

The effect of this amendment was that the policy now required “physical” injury to tangible property. Secondly, a loss of use constituted damaged property. Assuming that the property damage is tangible, the inquiry turns to whether there has been “physical injury”. In State v. Glen Falls Insurance Co., the Court opined that there is no coverage when property simply disappears or is lost. Absent evidence of actual destruction, there was no “physical” injury and hence no coverage.

D. 1986 DEFINITION

The 1986 revisions to the general liability policies did not substantially alter the “property damage” definition:

(a) Physical injury to tangible property, including all resulting loss of use of that property; or

(b) Loss of use of tangible property that is not physically injured.

The only substantive change involved the deletion of the term “destruction of” yet despite this change issues continue to be litigated. Questions continue to arise as to whether the property in question is tangible and the meaning of the term “physically injured”.

IV. OTHER EXCLUSIONS IN THE D&O POLICY:

A. THE IMPACT OF THE PHRASE “ARISING OUT OF”

One exclusion common to “property damage” exclusions in D&O policies provides as follows:

i. The Insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for loss in connection with any claim made against the Insured Persons:

…

x. based upon, arising out of, relating to, in consequence of, or in any way involving, … damage to or destruction of any tangible property, including loss of use thereof.

The potentially far reaching impact of the words “arising out of” was considered in Grayson v. Wellington Insurance Co. in construing the meaning and scope of the phrase “advertising injury” in a policy of commercial liability insurance. The insurer had declined to defend an action brought against its insured for copyright infringement, “piracy” and “acts contrary to honest industrial and commercial usage”.

The Plaintiffs’ corporations manufactured, marketed and distributed various “signal reception devices”, used to receive and descramble satellite signals without payment of subscription fees. These products were advertised in trade journals and at trade shows. In the underlying action, the Graysons were sued for the breach of various patent, copyright and trademark rights held by the Plaintiffs in Canada.

The Policy issued by Wellington contained the following definition of “Advertising Injury”:

“Advertising Injury” means injury arising out of an offence committed during the policy period occurring in the course of the Named Insured’s advertising activities, if such injury arises out of libel, slander, defamation, violation of right of privacy, piracy, unfair competition, or infringement of copyright, title or slogan.

In the Court’s view, the proper interpretation of the definition of advertising injury required that the insured demonstrate that the allegations in the underlying action involved (1) injury occurring “in the course of” the insured’s advertising activities and (2) injury that “arose out of” piracy, unfair competition or infringement of copyright.

In reaching its conclusion, the B.C. Court of Appeal noted a line of American cases which construed the definition so as to require a direct causal connection between the Insured’s advertising activity and the injury giving rise to the lawsuit.

While the competing lines of American authority seemed divergent, the Court of Appeal reconciled them in this way:

first, the fact that a product manufactured in breach of patent or copyright happens to have been advertised will not by itself bring the injury within the definition, the advertising will be regarded as merely “coincidental” to the wrong. Where, however, the Plaintiff in the underlying action alleges that it has suffered injury as a result of the infringer’s advertising activities, or where one of the remedies sought is the cessation of the Defendant’s advertising activities, those activities may be seen as causally linked to the Plaintiff’s injury, and the requirements of the definition will be met.

The same conclusion was reached by the State of Minnesota Court of Appeals in Amos v. Campbell. In Minkov v. Reliance Insurance Co., the Court concluded that the words “arising out of” denoted “originating from”, “having its origin in”, “growing out of”, “flowing from”, “due to” or “resulting from”. The Plaintiff had undertaken iron and steel erection work in connection with the construction of a fire station, including the installation of steel roof trusses. During the course of the work, a wall developed a crack and subsequently had to be demolished and replaced. The insurer refused to undertake the defence of the resulting suit, arguing that the damaged wall fell within an exclusionary clause of the policy, which read:

(1) Under Coverage B, with respect to Division 2 of the Definition of Hazards, to injury to or destruction of property arising out of the collapse of or structural injury to any building or structural injury to any building or structure due to excavation (including borrowing, filling or backfilling in connection therewith), tunnelling, pile driving, cofferdam work, or caisson work, or to moving, shoring, underpinning, raising or demolition of any building or structure, or removal or rebuilding of any structural support thereof;

The liability insurer took the position that, since the injury to the fire station was of a structural nature, it was excluded under the terms of the policy, which excluded injuries arising out of structural injury. The Court disagreed and concluded that the clause excluded “injury to property arising out of the collapse of or structural injury to any building”.

By analogy, a Court will likely require a causal connection between the impugned conduct of the D&O’s and the property damage for the exclusion to operate. However, the exclusion only operates for tangible property and leaves open the possibility of coverage being afforded for intangible property damage claims.

The seeming willingness to blunt the impact of the exclusion in the D&O context is illustrated by the decision in Board of Managers of Yardarm Condominium II v. Federal Insurance Company. The Plaintiff in the underlying action owned an apartment in a condominium complex. A fire in 1993 rendered the Plaintiff’s apartment uninhabitable during the 1993, 1994 and 1995 summer seasons. The Plaintiff’s insurer paid for the living expenses incurred for the first two years but denied the third year’s expenses on the basis that the reconstruction was not completed within a reasonable time. The Board was insured under an Association Directors and Officers Liability Insurance Policy issued by Federal. Federal denied coverage on the basis of the policy’s property damage exclusion. Federal would not cover any claim that was:

“directly or indirectly based on or attributable to, arising out of, resulting from or in any manner related to … Property Damage including loss of use thereof”.

The Court granted the D&O insurer’s motion to dismiss the insured’s action and the Court of Appeal agreed. The Court stated:

Notwithstanding the conclusory allegations of negligence in Aaron’s complaint in the underlying action, the Supreme Court properly concluded that the Property damage exclusion clearly and unequivocally applied to the underlying claim, which was indirectly if not directly, related to the property damage caused by the fire in 1993.

This decision needs to be contrasted with Nancy Clark v. General Accident Insurance, in which the Court reached the opposite conclusion. In Nancy Clark, a claim that directors of a condominium association failed to properly allocate proceeds of property damage claims resulting from Hurricane Hugo was not excluded under the D&O policy by means of a property damage exclusion. The policy wording specifically excluded coverage for any claim for:

(a) Personal injury;

(i) based on or attributable to bodily injury, sickness, disease or death of any person, or to injury to or destruction of any tangible property, including loss of use thereof; or for loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed;

Clark was a former director of the Mountain Top Condominium Association and brought the action because of the D&O insurer’s refusal to provide coverage for a lawsuit brought by condominium owners against the insured and other members of the association. The insured sought a declaration that coverage was available under a directors and officers liability policy and the Court granted the insured’s motion.

The D&O policy excluded “property damage” on the following terms:

(i) based on or attributable to bodily injury, sickness, disease or death of any person, or to injury to or destruction of any tangible property, including loss of use thereof; or for loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed;

The D&O insurer characterized the claims in the underlying action as being based upon or attributable to “injury to or destruction of any tangible property, including loss of use thereof,” as well as for claims “for anything other than money damages,” both of which were excluded.

While Hurricane Hugo and the damage wrought by it form part of the background to this case, the [underlying] action does not seek to recover for the physical injury to and destruction of their property caused by the hurricane. Rather, the lawsuit is based on and attributable to actions taken by the association and the directors and officers of that association, including failure to appoint an insurance trustee, failure to allocate the insurance proceeds properly, failure to allow plaintiffs to have their units properly maintained and repaired, wrongfully filing a notice of lien against Seipel’s condominium units, failure to hold an annual meeting, and failure to enforce many of the condominium by-laws, including the by-law for the restriction of the use of condominium units for residential purposes only. As a result of this conduct, or failure to act, the Seipels assert that they were damaged and are entitled to injunctive and monetary relief. … In sum, because the Seipel’s claims are not based upon injury to their property and the Seipels seek money damages, Clark is entitled to coverage under the D&O policy.

The Court in this decision was able to avoid the application of the property damage exclusion in its entirety by characterizing the claim as one related to the actions of the association’s directors. These two decisions highlight the importance of analysing not only the policy wording but the ability of the Court, or the insured, to recast the claim in a different light so as to afford coverage.

In Harristown Development Corp. v. International Insurance Co., the Court also denied the D&O insurer’s attempt to invoke the “property damage” exclusion. In this case, a developer filed suit naming Harristown Development Corp. (“HDC”) and its Vice-President as two of the Defendants. The suit sought to enjoin the condemnation of property the developer had acquired to redevelop. This action alleged HDC and its Vice-President attempted to take the Plaintiff’s property for a private, rather than public, purpose, in violation of Pennsylvania law. The Plaintiff alleged that the threatened condemnation was done to prevent competition with a private developer. The limited relief sought was injunctive in nature. The Plaintiff commenced a separate action setting forth an antitrust claim, charging the same Defendants with conspiring to monopolize the redevelopment of the relevant areas.

Among the defences relied upon by the D&O insurer was an exclusion for “Property Loss”, which read:

The Insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for loss in connection with any claim made against the Directors and Officers:

(c) based on or attributable to bodily injury, sickness, disease or death of any person or to damages to or destruction of any tangible property including loss of use thereof.

The Plaintiff’s property qualified as tangible property which was damaged to the extent that the Defendants prevented the Claimant from using the property for its contemplated purpose. The loss in profits, rental or otherwise, represented the damages sought. The Court stated:

The phrase “tangible property” is certainly broad enough to cover real property as well as personal property. However, we believe that plaintiff correctly asserts that some kind of physical damage to the property must occur before the exclusion can apply.

In this decision, the Court placed emphasis on the words “damages to or destruction of”. In the absence of actual physical damage, an insured is likely to find coverage.

The question arises as to whether a claim for the diminution of share value by shareholders would be excluded from coverage when that diminution appears to arise from property damage. The ‘arising out of’ language represents the widest exclusion for ‘property damage’ but will it operate to exclude an action commenced by a shareholder for the diminution in the value of their shares? For example, if a manufacturer of breast implants is sued for personal injury alleged to have been caused by those implants, the share value in that company will likely drop. A lawsuit at the hands of the shareholders may develop if the Directors are believed to have been responsible for failing to heed an expert’s advice to recall the product, for example. Again, the Court’s reasoning in Nancy Clark is instructive. Despite the breadth of the exclusion, a Court is able to characterize the action as one relating to the actions, or inactions, of the directors and not as one relating to property damage. The scope of the exclusion is immaterial if a Court is able to conclude that it simply does not apply.

B. THE EXCEPTION FOR SHAREHOLDER CLAIMS

A slightly narrower exclusion for “property damage” in a D & O policy reads as follows:

This insurance does not apply to:

(x) Claims arising out of or attributable to … damage to or destruction of any tangible property including loss of use thereof …. However, this exclusion shall not apply to any Claim made directly or derivatively by a security holder of the Corporation in his/her right as such provided that such Claim is brought totally without the solicitation, assistance, participation or intervention of any Insured(s) or the Corporation.

A direct claim is, for example, a claim by a shareholder for misrepresentation by the D&O’s in a securities prospectus. This type of action is an assertion of a right vested in a shareholder as against the party allegedly responsible for the shareholder’s damages. A derivative lawsuit, in contrast, is an action based upon a loss to the corporation but procedurally asserted on the company’s behalf by the shareholders because the corporation has failed or refused, for whatever reason, to seek redress. The corporation is a necessary party to the action and the relief which is granted is a Judgment against a third party in favour of the corporation.

Claims for misrepresentation can arise in the context of a loss to property. This is illustrated by the example of a mining company which constructs a dam to store toxic by-products created during the mining process. A collapse in the wall of a dam could send millions of cubic meters of toxic waste into the nearby countryside. The collapse then could result in substantial remediation expenses and a resulting interference with the mining operations, which in turn may result in the share price dropping. If the prospectus purports to constitute full, true and plain disclosure of all material facts relating to the company’s environmental due diligence, but the D&O’s had been apprised by their engineering consultants that the dam suffered from structural defects, a direct action by the shareholders against the Directors and Officers for misrepresenting the corporation’s true state of affairs in the prospectus could arise. In this hypothetical, the general liability policy might respond to pay the clean up costs and the D & O policy may be called upon to respond to the D & O’s resulting exposure for misrepresentation.

The wording of the “property damage” exclusion leaves open the possibility of coverage for (i) a claim for damage to intangible property, or (ii) a claim brought derivatively or directly for either tangible or intangible property damage. The reality of direct and derivative actions alone manifests the possibility of activating both a CGL and a D&O policy in a single loss, thereby ‘gutting’ the property damage exclusion.

C. COVERAGE FOR “POLLUTION CLAIMS” NOT ENTAILING PROPERTY DAMAGE

Some Canadian D&O insurers will expressly grant coverage to corporate executives for claims of pure economic loss that are secondary to, or consequential upon, a property damage claim. An example of one such wording reads as follows:

A “Pollution Claim” means a Claim made against any Executive which alleges a violation of the Canadian Environmental Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 16 (4th supp.), or the Environmental Protection Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E-19, the regulations promulgated thereunder and amendments thereto, or similar provisions of any Canadian provincial law.

The practical effect of this extension in coverage is to cover any pure economic loss unrelated to the direct property damage portion of the loss. This is achieved by means of an exclusion that reads:

The Insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for Loss in connection with any Claim made against an Insured:

…

(i) damage to or destruction of any tangible property, including, inter alia, asbestos or asbestos-containing materials, or acid rain conditions;

D. THE SCOPE OF THE LANGUAGE “IN CONNECTION WITH”

The first three of the exclusions under consideration in this paper have in common the use of the phrase “in connection with”. The insurer excludes liability for any loss in connection with property damage. Based on existing case law in other legal contexts, this phrase is arguably ambiguous enough to afford coverage for a property damage claim. In Gottardo Properties (Dome) Inc. v. Toronto, the Court was asked to consider whether the licensees of Skyboxes at the Skydome in Toronto were liable for business assessment because of their use or occupancy of the Skyboxes. The relevant portion of the Assessment Act provided:

Irrespective of any assessment of land under this Act, every person occupying or using land for the purpose of, or in connection with, any business mentioned or described in this section, shall be assessed for a sum to be called “business assessment” to be computed by reference to the assessed value of the land so occupied or used by that person as follows: …

The boxholders used the Skyboxes to promote their business interests by inviting clients, customers and others to use the boxes to enjoy their use. The Court did not find them liable for business assessment and had this to say about the phrase “in connection with”:

To determine whether occupancy or use of land is for the purpose of or in connection with a business … jurisprudence has adopted the preponderant purpose test. McIntyre J. explained this test in Regional Assessment Commissioner v. Caisse Populaire de Hearst Ltee, [1983] 1 S.C.R. 57 at 71:

The preponderant purpose test has had wide – in fact almost complete – acceptance in Ontario and certain other provinces since the decision in the Rideau Club case. Essentially it has been based upon a consideration of whether the activity concerned is carried on for the purpose of earning a profit or for some other preponderant purpose. If the preponderant purpose was other than to make a profit, then even if there were other characteristics of the organization, including an intent in some cases to make a profit (see Maple Leaf Case), it would not be classed as a business.

The preponderant purpose test, when applied to an exclusion in a D&O policy is most troublesome for the first of the two exclusions under consideration. The argument advanced by an insured will likely be that the preponderant purpose of the Claim is to advance Loss, not for property damage, but, for example, Loss resulting from the actions or in actions of the Directors themselves. Similarly, the language may afford an argument that the Claim is not really about Loss resulting from property damage but is one for other Losses, for example economic loss. By contrast, the third exclusion, by employing language such as “or in any way involving”, for example, provides an insured with a narrower scope of coverage. The fourth exclusion similarly provides a narrower scope of coverage by excluding claims “arising out of or attributable to” property damage.

E. THE EXCLUSION “FOR DAMAGE TO PROPERTY”

Finally, the narrowest version of the exclusion for “property damage”, is exemplified below:

The Insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for loss in connection with any Claim made against the Insured:

(x) for bodily injury, sickness, disease, death or emotional distress of any person, or damage to or destruction of any tangible property including loss of use thereof; …

The term “damage” has been treated by the Courts as narrower in its scope than the term “injury”. Some versions of this exclusion often do not, for example, specifically encompass “physical injury to property damage”. Thus, losses other than for tangible property, for example, the loss of share value, the loss of company goodwill, or, the loss of intellectual property protection which is an inchoate economic right, could be afforded coverage from the standpoint of the D&O policy. The problems inherent to this wording are twofold. Firstly, there is not the breadth in the wording to cover intangible property. Secondly, if the words “damage to or destruction of” are more restrictive or narrower in scope than the term “injury”, then there is room to argue that an “injured intangible” or perhaps even an “injured tangible” is covered from the standpoint of the D&O policy.

F. EXCLUSION CLAUSES AND RELATED CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES

Property damage will often be accompanied by consequential economic loss. For example, a damaged building might have to be evacuated and rents thereby lost. The lost rent is likely excluded by operation of the phrase “including loss of use thereof” in a D&O policy’s property damage exclusions. However, the question arises as to whether the property damage exclusion in a D&O policy will operate to exclude claims for other consequential losses in addition to the claim for the property damage itself. The principles of construction of a policy of insurance dictate that an exclusion will be construed narrowly against the insurer. This is illustrated by the decision in Murray v. State Farm Fire and Casualty Co., in which the Plaintiffs suffered a water leak in their home emanating from a break in a hot water pipe. The leak was caused by exposure to moisture and acidic soil. The insurer successfully moved for summary Judgment by relying on the policy’s exclusionary provisions. Ultimately, the Court of Appeal concluded that there was no coverage for any of the costs incurred by the Plaintiffs. However, during the course of its reasoning the Court stated what is perhaps an obvious conclusion:

If, however, the Murrays suffered consequential loss as a result of the corroded pipe and that consequential loss or “ensuing” loss is not excluded under another provision of the Policy, the loss is covered.

It is here that the frailties of the wording of a D&O policy’s exclusion clauses will bear on the coverage afforded (or not) to consequential losses. The Nancy Clark case is again worthy of consideration. While that case is not so much concerned with the ‘gaps’ in an exclusion clause as it is about the ability of a Court to circumvent the clause in its entirety, clearly it can be employed to find coverage for both property damage claims and consequential losses.

The narrowest exclusion under consideration in this paper (the “for property damage”) exclusion is most vulnerable to a claim of coverage for consequential losses. While the exclusion will likely operate to exclude losses to tangible property, the deliberate use of the word tangible leaves open the real possibility of finding coverage for consequential losses such as the economic loss suffered when share values drop due to the actions or inactions of corporate directors. The employment of this narrow exclusion will leave the door open to an insured and a Court to find coverage where none was likely contemplated by the insurer.

V. CLAIMS FOR PURE ECONOMIC LOSS

The purpose of the second section is to provide a synopsis of the leading cases which, taken together, delineate the line between claims for pure economic loss and claims for property damage.

Privest Properties Ltd. v. Foundation Co, of Canada Ltd., [1991] BCJ No. 2213 (SC)

In this action, the insured was a general contractor who sought a declaration that one or more of its six general liability insurers ought to pay the legal costs incurred defending the Plaintiffs’ legal action. Each of the liability insurers resisted the application on the basis that the action fell outside of coverage. Foundation had been retained by the Plaintiff to renovate a building in Vancouver. As part of the renovations, a spray fireproofing material containing asbestos was applied to parts of the building.

Each of the six insurers issued policies with differing insuring agreements for property damage. The wordings of the various liability insurers follow.

1. The Insurer agreed to pay on behalf of the insured:

All sums which the Insured shall become obligated to pay by reason of the liability imposed by law and/or assumed under any contract or agreement for damages (including damages for care and loss of services) because of:

b. Damage to or destruction of property, including loss of use thereof, and consequential loss, caused by accident or due to an occurrence as defined herein, which takes place anywhere during the policy period.

2. The Insurer agrees to pay on behalf of the Insured all sums which the Insured shall become legally obligated to pay by reason of the liability imposed by law upon the Insured or assumed by the Insured under contract … for damages because of

(c) (i) injury to or destruction of property, including loss of use thereof, or loss of use of property which has not been physically injured or destroyed provided such injury or loss of use is caused by an accident; or

(ii) injury to or destruction of tangible property, or any loss of use thereof due to an occurrence (as defined herein)

during the policy period, subject to the limits liability, exclusions, conditions and other terms contained herein.

3. [The Insurer shall] pay on behalf of the Insured all sums which the Insured shall become obligated to pay by reason of the liability imposed by law upon the Insured or assumed by the Insured under contract for damages because of:

Coverage B – Property Damage Liability

(i) Physical injury to or destruction of tangible property including the loss of use thereof and at any time resulting therefrom or;

(ii) Loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed,

provided such loss of use is caused by an accident or occurrence (as defined herein)

occurring during the policy period and arising out of the construction operations of the Insured as described in the Declarations and other terms and conditions contained herein.

4. The Insurer agrees to pay on behalf of the Insured all sums which the Insured shall become legally obligated to pay as damages:

2. Property Damage Liability

because of damage to or destruction of or loss of use of tangible property caused by an occurrence during the policy period.

The term “Property Damage” was not defined in any of the four wordings.

5. subject to the limitations, terms and conditions hereinafter mentioned, to pay on behalf of the Insured all sums which the Insured shall be obligated to pay by reason of the liability

(a) imposed on the insured by law, or

(b) assumed under contract or agreement by … the … Insured …

for damages, direct or consequential, and expenses, all as more fully defined in the term “Ultimate Net Loss” on account of:

…

(ii) Property damage,

caused by or arising out of each occurrence happening anywhere in the world.

In the excess policy wording, property damage was defined as being “loss or direct damage to or destruction of tangible property (other than property owned by the Named Insured). The grant of coverage stated

6. pay on behalf of the Insured ultimate net loss excess of the retained limit as hereinbefore defined, which the Insured shall become legally obligated to pay as damages by reason of the liability imposed upon the Insured by law, or assumed by the Insured under contract because of:

…

(b) property damage …

The excess insurer was liable only for the ultimate net loss excess of the Insured’s retained limit defined as either:

1. the total of the applicable limits of the underlying policies listed in the Schedule of Underlying coverages hereof and applicable limits of any other underlying insurance providing coverage to the Insured: or

2. the amount stated in Item II of the Declarations as the result of any one occurrence not covered by such underlying policies of insurance: and then up to an amount not exceeding the amount as stated in Item I of the Declarations as the result of any occurrence.

The term “Property Damage” was defined as:

(1) physical injury to or destruction of tangible property, which occurs during the policy period, including loss of use thereof at any time resulting therefrom; or

(2) loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed provided such loss of use is caused by an occurrence during the policy period.

The first two wordings were considered broad enough by the Court to find coverage for a loss characterized as “pure economic loss”. The remaining four were not triggered by the Plaintiffs’ claim. The general liability insurers collectively maintained that the claim as advanced by the Plaintiffs was for pure economic loss rather than for damage or physical injury to property. Counsel for the respective parties referred the trial judge to some 250 legal cases. None of the Canadian authorities, in the Court’s view, supported the conclusion that the application of asbestos to the building constituted “damage to tangible property”.

So far as Canadian law is concerned, it seems clear that unless there has actually been personal injury or damage to other property, the cost of repairing or replacing defective work is considered to be pure economic loss rather than damage to property.

The sample principle is apparent in recent English case law; D&F Estates Ltd. and others v. Church Commissioners for England and others.

There is, however, judicial support for a differing conclusion in American jurisprudence. In one of the Asbestos Insurance Coverage Cases, Judge Brown of the Superior Court of the State of California, observed that:

Although numerous legal theories are advanced in the building cases, the claimants generally seek compensation for the sums they must expend to eliminate the alleged health hazard of ACBM [Asbestos Containing Building Materials] in their buildings and for the diminished value of their buildings …

Whether the incorporation of ACBM in a building can constitute property damage has not been addressed by California Courts to date.

Under California law generally, incorporation of a defective product is considered property damage for insurance coverage purposes if it results in a diminution in value of the larger property.

…

Carriers using the 1973 form maintain that even if it is some type of property damage, incorporation of a defective product is not physical injury to property. The Court disagrees. Economy Lumber holds that incorporation without physical harm to the larger structure can constitute physical injury. In Economy Lumber, the Court found coverage in an analogous situation under a post-1973 physical injury policy …

In addition, it makes sense to view incorporation of ACBM as a physical injury. Once installed, ACBM is physically present in the buildings and affects them in a physical way, as opposed to an intangible, non-physical manner.

In Privest, the building owner claimant had not made any express allegations of physical injury or damage to any part of the building or of damage to or loss of any other tangible property. Therefore none of the claims advanced, if proven, would constitute physical injury or damage to or loss of use of tangible property. No duty to defend therefore flowed.

However, the Court concluded that the claims advanced alleged facts which, if proven, would constitute “injury to property” in the sense of an infringement to intangible property or an incorporeal right. As such, they fell within the terms of clause (c)(i) of the second insuring agreement, noted above.

In addition, the Court found coverage under the first policy, above. The claims alleged facts which would constitute “damage to property”. While the word “damage” may have a narrower meaning than that of “injury”, they were quite similar, in the Court’s view, if not synonymous. In the context of a liberally interpreted insuring agreement, the Court chose to resolve that ambiguity in favour of the insured.

Bird Construction Co. v. Allstate Insurance Co. of Canada, [1996] 7 WWR 609 (MBCA)

In this case, the Court found for the insurer and concluded that the allegations in the underlying action did not amount to “property damage” as defined by the policy of insurance. The insured was a general contractor. In the underlying action, it was alleged that a building constructed by the insured was inherently dangerous. In 1989, a substantial section of the building’s exterior cladding fell to the ground from the ninth floor. As a result of the inspection that followed, the condominium corporation had the entire cladding removed and replaced at a cost of $1 million. The cost of that correction was claimed from the insured. In the underlying action, it was not alleged that the building’s condition caused third party bodily injury, or, third party damage. In the Insurer’s view, the claim was therefore for “pure economic loss“, both from a tort and coverage perspective.

The Court at first instance granted a declaration obliging the liability insurer to indemnify for the claim. The general liability insurer appealed that determination of the Manitoba Court of Appeal.

The insuring agreement in issue provided:

[The insurer] will pay on behalf of the Insured all sums … which the Insured shall become legally obligated to pay as compensatory damages because of

…

Property damage

caused by an occurrence.

“Property damage” means (1) physical injury or destruction of tangible property which occurs during the policy period, including loss of use thereof at any time resulting therefore, or, (2) loss of use of tangible property which has not been physically injured or destroyed provided such loss of use is caused by an occurrence during the policy period.

The Court of Appeal concluded that the underlying tort claim was not one for damages because of bodily injury as none was in fact alleged. Nor did the Court conclude that it was one for damages because of property damage, as defined by the policy. The Court observed that the losses claimed in the underlying action fell clearly within the category of “pure economic loss” for tort purposes. Loss of use was the only “pure economic loss” covered by the policy. No claim for loss of use was advanced against the insured and no defence was therefore owed.

Alie v. Bertrand & Frere Construction Co. (2000), 30 CCLI (3d) 166 (ONSC)

In this case, the Court had to consider whether remediation costs caused by the incorporation of a defective product amounted to a case of “pure economic loss”. The Plaintiffs in this action were homeowners whose concrete foundations deteriorated shortly after the homes were built. The concrete for all of the homes was poured by the general contractor. The concrete supplier, Lafarge, sold the cement powder and fly ash used in the batching of the concrete. The foundations built from the concrete ultimately evidenced major structural deficiencies. The only viable solution for the homeowners was to replace their foundations and an action was commenced for recovery of that expense. The insureds, in turn, sought coverage under their general liability policies.

23 insurers had each issued general liability policies to one of the two Defendants. The challenge for the Ontario Court was “to interpret these insurance contracts using the guidance of the jurisprudence to arrive at a common sense result”.

The general contractor sought indemnity for all damages awarded to the Plaintiffs, except for the actual costs of the concrete used to replace the deteriorating foundations. All of the general liability policies had an “occurrence” based property damage endorsement. The insurers undertook to pay on behalf of the insureds all sums which the insured became legally obligated to pay for damages as a result of an occurrence. The insuring agreements provided coverage for “any injury to or destruction of real or tangible personal property”.

The Ontario Court concluded that the cause of the loss was the insertion of fly ash in the concrete mix, resulting in a deleterious chemical reaction. The liability insurers argued that the costs of replacing the concrete amounted to pure economic loss and thus did not fall within coverage.

The general contractor took the position that the defective liquid concrete was made into residential foundations by the owners or the contractors and the concrete formed merely part of the foundation. The foundations involved the pouring and shaping of the concrete, together with the forms containing tie rods, reinforcing steel and anchor bolts. The Court stated:

Whether or not there is coverage will depend on the facts of each case. Clearly if the defective product becomes part of the whole of a third parties product, or is incorporated in a third parties product and can’t be removed or repaired without either rendering the third parties product useless or damaging it, the Courts have concluded that that is property damage and coverage will follow.

In following the sequence of events here, insertion of Lefarge’s faulty FA into Bertrand’s concrete would result in property damage suffered by a third party, that is Bertrand. Obviously, the problem cannot be resolved by attempting to remove the FA from Bertrand’s concrete. I would have no difficulty, therefore, in concluding that there had been property damage resulting in coverage.

…

This situation is much different than the cases cited dealing either with insulation containing asbestos or the exterior cladding of the building. The structural integrity of the buildings in those cases was never threatened. In this case, the faulty concrete became incorporated in the foundation and the faulty foundation was incorporated into the home and the very structural integrity of these houses is threatened. If the foundations are not replaced they will collapse. This is not the case with faulty exterior cladding.

The Court therefore had no difficulty in concluding that “property damage”, as defined in the policies, embraced much of the tort damages claimed by the homeowners.

To summarize the current Canadian law, unless there has actually been third party personal injury, or, damage to other property, the cost of repairing or replacing defective work is considered to be pure economic loss rather than damage to property. However, should the insuring agreement contain the more broadly interpreted phrases “injury to property” or “damage to property” coverage for claims concerning intangible property or incorporeal rights may exist. If the tort is characterized as “pure economic loss”, then narrow wordings such as “physical injury to tangible property” generally do not attract coverage whereas the broader wordings like “damage to property” can attract coverage.

VI. AREAS OF CONVERGENCE BETWEEN THE D&O AND GENERAL LIABILITY POLICY

The most obvious areas of convergence between a CGL and a D&O policy arise from the express words of the policy itself. In the case of grants of coverage for pollution claims, or, the narrowing of exclusion clauses to cover a company’s D&O’s for actions brought by shareholders, either directly or derivatively, there is the risk of coverage under both a general liability and D&O policy for losses resulting from the same risk.

Secondly, as the American decision in Nancy Clark illustrates, a Court can simply bypass the “property damage” exclusion in its entirety by characterizing a claim as resulting from the actions of the directors, not from “property damage”. That being so, it is not difficult to envision a loss triggering both a CGL and a D&O policy. In the example of the mining company, above, the CGL will respond to the cleanup costs. An action commenced against the directors for their failure to disclose any known environmental problem could well result in coverage under the D&O policy.

However, of primary concern to the D&O insurer is the ambiguity in the wording of its exclusion. If the D&O policy uses a narrow exclusion (“physical injury to tangible property”) that wording will exclude the narrowest range of claims. In other words, claims not involving physical injury to tangible property could attract coverage. The use of the broadest term (“damage to property”) excludes from coverage any property damage claim, whether or not the property is tangible or physically injured.

The narrowest coverage afforded under a D&O policy is the wording which utilises the “arising out of” language in the “property damage” exclusion. The language of this clause is the most likely to exclude any claim for “property damage”. In addition, if the corresponding general liability policy has the language of narrowest coverage (i.e. “physical injury to tangible property”), there is little likelihood of convergence.

The third D&O exclusion considered earlier in our analysis (the “for property damage” exclusion) provides the broadest of coverages available, as this wording will often not exclude the loss of an intangible property right. The likelihood of convergence with a general liability policy is enhanced if the wording of the CGL is of an older variety and provides coverage for damage to “property” without restricting the term to tangible property. For example, a loss affecting an intangible property right, such as a loss in share value, is one which can threaten to trigger both a CGL and a D&O policy.

The convergence between the general liability policy and the D&O policy is most likely to arise from a narrow definition of “property damage” in the D & O policy, such that fewer claims are excluded from coverage, and in contrast, the somewhat broader definitions of “property damage” in the older general liability policies which afford coverage to both intangible and tangible property damage claims.

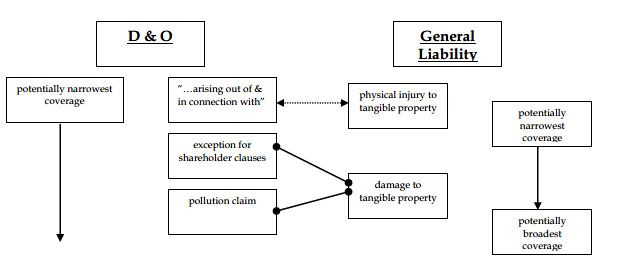

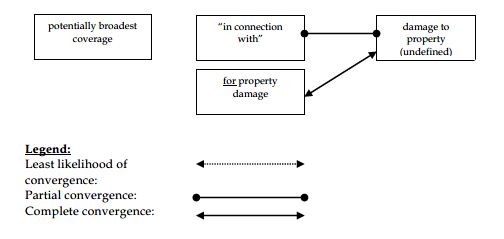

The following diagram is useful in illustrating the degree of potential overlap between the two policies:

VII. CONCLUSION

Experience supports the conventional wisdom as to the coverage for property damage claims and CGL and D&O policies. Typically, it is the CGL insurer who bears the brunt of this type of loss. However, conventional wisdom must give way to the explicit wording of D&O policies which allow for direct or derivative actions by shareholders and pollution claims. Secondly, Courts, as in Nancy Clark, are not adverse to recasting a claim so as to find coverage under a D&O policy. Finally, the wording of these exclusions is often ambiguous. As that ambiguity will be resolved in favour of the insured, coverage under a D&O policy for property damage claims can emerge. In the end, it is the D&O insurer who is likely to discover that it has accepted more risk than was originally intended.