July 1, 2001

Handling “Cross-Border” D&O and EPL Claims

HANDLING “CROSS-BORDER” D&O AND E.P.L. CLAIMS INVOLVING CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES

Eric A. Dolden and Susan Rutherford

July 2001

(Updated 2014)

CONTACT LAWYER

| Eric Dolden |

| 604.891.0350 |

| edolden@dolden.com |

I. INTRODUCTION: KEY DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE U.S. AND CANADA FOR THE D & O INSURER

As a result of the passage of legislation creating direct liability for directors and officers (“D & O’s”) in Canada, and as a result of increased Canadian corporate involvement in the U.S. money market, lawsuits against Canadian D & O’s are increasing in both frequency and severity. Canadian D & O exposures present a business opportunity and a legal challenge to insurers. In effect, a race is now being played out to see which insurer can most competitively and effectively respond to the scope and severity of the Canadian D & O claims environment. Whereas one could probably say that U.S. insurers have honed their domestic D & O programs to a level of comfort and familiarity; the companion Canadian D & O programs are only just now moving off of the drafting tables and in to the marketing arena for the test of real claims coverage. In this context, the process of putting together effective Canadian programs has to be seen as both an anxious and exciting time for D & O underwriters.

The purpose of this paper is to identify the key issues confronting the U.S.-based D & O insurer that is wanting to address exposures in the Canadian market, and conversely, the Canadian insurer confronting exposures in the U.S. market. The paper’s focus is to discuss the substantive differences in D & O law in each jurisdiction; and to elaborate on underwriting experiences to date, in responding to such differences. The discussion is organized under the following topics:

- The current Canadian approach to allocation;

- Statutory regulation of D & O policies;

- Status of the D & O who is an “innocent co-insured”;

- Comparative scope of coverage;

- Forum non conveniens and the D&O insurer’s use of anti-suit injunctions;

- How corporate reimbursement of D & O’s in Canada differs from the U.S.;

- The growth of employment practices liability insurance in Canada.

The goal of the paper is to familiarize American D & O insurance underwriters with some of the unique Canadian D & O exposures, and to suggest underwriting methods and litigation strategies by which these unique exposures can be managed.

II. THE CURRENT CANADIAN APPROACH TO ALLOCATION

A key issue confronting D & O insurers in recent years has been the allocation of defence costs and settlement amounts between insured and uninsured party defendants. The issue has been particularly prominent in the D & O context, due to the fact that under a standard D & O policy the liability of the corporate entity is not insured. Standard coverage under a D & O policy is limited to “corporate reimbursement”, and is usually delineated by one or both of two standard insuring agreements:

1. The first insuring clause indemnifies the corporation, to the extent that the corporation must indemnify its own directors and officers for their own individual liability, either for damages or other relief, or for the costs of defending, or both.

2. The second insuring clause indemnifies the D & O’s directly if the corporation is unable to do so.

As underwriters in this field well know, neither of these insuring agreements responds to the corporation’s own liability. All of the insurance money flows through to the D & O’s.

Thus, when both the insured D & O’s and the uninsured corporate entity are sued, the issue will often arise as to how the bill for defence costs and settlement amounts will be allocated, as between the insured D & O’s, and the uninsured corporate entity. Can the insurer limit its liability to just the proportionate liability of the insured D & O’s? How would proportionate liability be determined, in any event? The issue can be particularly difficult to sort out when one defence counsel is retained to represent both the insured and the uninsured interests.

As American underwriters will be aware, the issue of allocation has been the subject of vigorous litigation in the United States, since approximately 1986. Out of that litigation there have emerged several approaches for resolving allocation problems. In contrast to the U.S. experience, however, the issue is a relatively novel problem to Canadian courts, and hence, the issue as to which approach will be adopted in Canadian jurisdictions is only now being litigated. Allocation remains, to some degree at least, an open question in Canada. The purpose of this section of the paper is to discuss the Canadian position.

The American approach, from 1986 until 1995, accepted that any allocation exercise between insured and uninsured parties, must have regard to each party’s “relative exposure”, “relative benefit” and the “factors considered applicable in the circumstances”.

A commonly cited text authority for the factors to be considered applicable is Knepper & Bailey’s (5th ed.) popular text on the subject. The factors identified there are:

the identity, as an individual, an entity, or as a member of a group, of each beneficiary and the likelihood of an adverse judgment against each in the underlying action;

(a) the risks and hazards to which each beneficiary of the settlement was exposed;

(b) the ability of each beneficiary to respond to an adverse judgment;

(c) the burden of the litigation on each beneficiary;

(d) the “deep pocket” factor and its potential effect on the liability of each beneficiary;

(e) the funding of the defense activity in the litigation and the burden of such funding;

(f) the motivation and intentions of those who negotiated settlement, as shown by their statements, the settlement documents and any other relevant evidence;

(g) the benefits sought to be accomplished and accomplished by the settlement as to each beneficiary, as shown by the statements of the negotiators, the settlement documents and any other relevant evidence;

(h) the source of the funds that paid the settlement seem; and

(i) the extent to which any individual defendants are exempted from liability by state statute or corporate charter provisions; and

(j) such other similar matters as are peculiar to the particular litigation and settlement.

In 1995, considerations integral to “relative exposure” and “relative benefit” were, however, eliminated in several U.S. jurisdictions as a result of three successive appellate level decisions (“the trilogy”), which adopted what is referred to as the “larger settlement rule”, a rule espousing the principle that there should be no allocation away from an insured party unless, due to the liability of the uninsured party, the settlement amount was made larger. In the result, the trilogy has made it difficult for an insurer in the United States to achieve any significant “allocation away” of costs or settlement amounts.

The issue of allocation has just recently been before the courts in the Province of British Columbia, in the case of Coronation Insurance v. Clearly Canadian Beverage Corporation et al.

The issue in Clearly Canadian involved the question of allocation of a settlement, as between the insured D & O’s and the uninsured corporation, the B.C.-based company, Clearly Canadian. The underlying action, which had been litigated in the State of California, consisted of a securities action brought against the company and its D & O’s. Both the D & O’s and the uninsured company had been represented in the suit by the same defence counsel. (Typically, the policy had no “duty to defend” provision.) While the D & O policy stipulated that defence and investigation costs were to be allocated on the basis of the “principle benefit” rule, the policy was silent with respect to allocation of settlement amounts.

A settlement was entered into, following approval of the amount by the D & O insurer on a “non-waiver” basis. The D & O insurer then advanced some funds on account of the settlement, but raised the issue of allocation, arguing that some amount ought to be allocated away from the D & O insurer to the uninsured corporate entity, particularly since there was evidence that the company had had its own distinct reasons, unrelated to the company’s liability in the action or any conduct of the D & O’s, for wanting to have the litigation settled. The insurer argued that by approving the settlement on a “non-waiver” of rights basis, it had retained the right to contest the proper amount to be funded in view of any subsequent allocation exercise.

The parties were unable to agree on the allocation issue and the insurer commenced a Petition in the British Columbia Supreme Court to have the matter adjudicated.

Following the initial hearing, the B.C. Supreme Court observed that the issue of allocation has not before been litigated in a D & O context in Canada. The court further noted that, while there had been American consideration of the issue, no single approach to allocation could be said to “govern” the U.S. cases, only whatever approach was “equitable in the circumstances”. The court noted that certain approaches seemed to be more relevant to the allocation of settlement payments than to the allocation of defence costs.

The court specifically observed that the problem of allocation arose on the facts of the case, due to the fact that the liability of the D & O’s and the corporation might not be concurrent in all cases. In describing the underlying action in California (which alleged violations of the United States Securities and Exchange Act of 1934) and its impact on the insurance question, the court stated,

The legislation creates liability for persons as well as for corporations that violate its provisions. It creates direct liability for corporations, meaning a corporation can become independently liability [sic] for the activities of its directors, officers, and others who conduct its business; it does not derive liability only from their liability. Those who are responsible for a corporation’s liability may be able to raise defences that are not available to the corporation based on considerations like the extent of their personal involvement in the wrongdoing, their lack of intent to deceive, and the limited control they exercised over others who bear primary responsibility for the violations. What is important here is that the liability of a corporation and that of its directors and officers whose conduct is the subject of a claim will not necessarily always be concurrent.

The court therefore agreed with the insurer that the potential existed for liability of the corporation without the liability of the D & O’s, and further, that there could be liability to the corporation as a result of conduct of persons not insured.

In approaching one of the threshold issues underlying the argument for allocation, the court adopted a common sense approach. The court held that the duty to allocate a settlement amount was not something that was contingent upon there being a contractual provision between the parties. In response to an argument put forth by the company that requiring allocation would be tantamount to ‘implying into the contract a provision reducing coverage’, the court stated:

The contention that allocation would require implying a term in the policy is also, in my view, not well founded. The requirement to allocate settlement amounts exists, not because of terms whereby insured and insurer may agree to it, but because it is essential to limiting the insured’s obligations to indemnify to the coverage the policy provides: Nordstrom (p. 6) and Caterpillar (p. 8). Allocation is an equitable necessity. It does not rest on a contractual agreement per se.

The parties to a contract of insurance may stipulate for an early allocation and provide for the way certain expenses will be borne – what are insured – as they have done in this policy with respect to defence costs, and they may covenant to use their best efforts to allocate expenses between insured and uninsured interests: Safeway p. 18, but I do not consider the absence of terms of that kind can possibly mean that there can be no allocation once the insurer’s consent to a settlement is given as the directors and officers contend.

Allocation between what is insured and what is not has long been a part of insurance. I do not consider any term need be implied in [the insurer’s] policy to permit the allocation of settlement amounts even though there is a clause that provides for the early allocation of defence costs.

Ultimately, however, in deciding on the specific approach to be taken in the case, the court adopted the “larger settlement” rule, as set out in the trilogy, and modified by the Caterpillar decision, supra. The court concluded on the allocation issue:

I conclude there could be an allocation of the settlement amount in this case, but only to the extent it can be said that the liability that may have been established against the corporation would not have been entirely concurrent with any liability that may have been established against the directors and officers. That, it seems to me, is what the coverage afforded requires and what would be entirely fair and equitable. I consider the allocation for which the insurer contends could well deprive Clearly Canadian of some of the insurance it purchased and lead to a result that would be manifestly unfair.

The court did not agree that simply because the policy specified that defence costs would be allocated according to the “principle benefit” rule, that settlement amounts ought to be allocated upon the same principle. The court also did not agree that considerations underlying adoption of the settlement ought to be considered as a factor in determining the allocation issue. The court relied on the following statement of the court in Caterpillar:

We also believe that a protracted pursuit of the motivations underlying a settlement… is not necessarily the best way to resolve coverage disputes: The question at issue is whether the insurance policy covered certain claims, not the metaphysical underpinnings of why a corporation or its directors and officers may have acted as they did.

And from Nordstrom:

We reject [the insurer’s] contention that allocation in this case should also depend on an analysis of factors other than liability, such as negative publicity, that might have had a practical effect on the amount of the settlement. Although such factors have been applied by other courts, we decline to require consideration of such factors, which likely would lead to protracted discovery on issues wholly outside the context of liability…

At the first instance, the court did not address what sort of allocation ought to result, where neither the corporation nor the D & O’s had any potential liability.

The insurer appealed to the B.C. Court of Appeal, hoping to persuade the higher court to adopt the principle benefit rule; however, in Reasons released in January, 1999, the Court of Appeal affirmed the trial court’s decision.

The appeal judgment sends a strong message to insurers that allocation of settlement amounts will only be granted on the basis of the “larger settlement” rule, unless otherwise specifically provided for in the contract. The Court of Appeal rejected all other “equitable” arguments for allocation, and even went so far as to say there was no cause of actions for allocation, beyond an action based on principles of contract.

The court reviewed the insurance contract in question and concluded that the contract’s silence on the issue of allocation of settlement funding supported no more and no less than an argument for “full insurance coverage, “ i.e. the insurer to cover all settlements of covered liabilities, except insofar as such settlements were made larger as a result of liabilities not covered by the insurance contract which are caused by the presence of non-insured defendants. The court found that the “larger settlement” rule was consistent with the B.C. Court of Appeal’s holding in Continental Insurance Co. v. Dia Met Minerals Ltd., finding that “… at least where the insurer does not have conduct of the defence, costs incurred to defend a covered claim are properly segregated from those incurred in respect of a non-covered claim.” In the result, the court remitted the matter to the trial court for a determination of “…the extent, if any, to which the settlement of the underlying action was increased by the joinder of CCB as a defendant.”

The Court of Appeal agreed that the allocation issue remained open, given that the insurer had only agreed to the settlement on a “non-waiver” basis, thereby retaining its right to argue the allocation issue.

With respect to the insurer’s arguments that the “principle benefit” rule ought to apply, the court commented that the insurer’s argument could be encapsulated into two themes: 1) the theme of “unfairness”, i.e. that it would be unfair to allow the uninsured entity to effectively have a “free ride” on the insurance of the D & O’s; and 2) the theme of “reasonable expectations”, i.e. that the parties to the contract should be taken to have expected the settlement funds would be allocated according to the Knepper & Bailey factors.

With respect to the theme of “unfairness”, the Court found that it was neither objectively “fair” nor “unfair” that the uninsured company might benefit from the D & O’s coverage, if such benefit were simply a side-effect of the D & O’s having the full benefit of the coverage which the court found they had bargained for. The Court concluded that the very existence of the policy itself provided the “juridical reason” for the benefit which had resulted. At the forefront of the Court’s reasoning was a consciousness that the uninsured company was in fact an “insured” in other circumstances, and the Court resiled from the insurer, in the court’s words, “attempting to obtain restitution from an insured (CCB), in order to pay less than full indemnity under one policy of insurance.” The Court denied that the right of contribution existing at common law between insurers, arising from the common law rule that as a general rule of indemnity an insured may not recover more than his loss, was an appropriate comparator or rationale for justifying the allocation or reimbursement sought by the insurer from the uninsured company on the facts at hand.

With respect to the theme of “reasonable expectations”, the Court also found that there was no foundation for such an argument, where the policy was silent on the issue of allocation of settlement amounts, and otherwise was worded to cover “all Loss” without qualification or contemplation of the “principle benefit” rule, factors underlying the settlement, considerations of “direct” or “derivative” liability, or otherwise. Consistent with general insurance principles of contra proferentem, the court adopted a liberal construction for coverage and a strict construction on limits to coverage. The clear message to insurers was, if you want to allocate a settlement, say so clearly in your policy!

To conclude then: the Court of Appeal affirmed that aside from any contractual provisions stipulating for allocation of a settlement liability, allocation may be available, but only to the extent that the settlement can be broken into covered and non-covered claims. Where the settlement is larger due to non-covered liabilities (resulting from the addition of uninsured parties), allocation is appropriate on the grounds that an insurer is only bound to provide such coverage as is set out in the contract.

It is interesting to note by way of comparison, that the New Zealand courts have also recently been grappling with allocation issues. Just last year, a case was appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, New Zealand Forest Products v. New Zealand Insurance Co. Ltd. The case considered a dispute over the allocation of defence costs.

The New Zealand Court of Appeal had earlier approved the more traditional approach to allocation, i.e. the approach referencing “relative benefit”, “relative exposure” and “factors considered applicable in the circumstances”, and had even approved the factors identified in Knepper & Bailey (5th ed.), listed supra. In the result, the Court of Appeal found that the insurer was only responsible to pay its “proportionate share” of the defence costs.

On appeal, the House of Lords ruled that a proper determination of the issue had to be focused on a proper construction of the policy, rather than on applying general principles of allocation:

Their Lordships are not persuaded that the guidance given in relation to the one class of case is necessarily applicable to the other. Furthermore there seems to Their Lordships to be a possible danger in concentrating on the case law in that the problem might seem to be one of applying principles of general application rather than construing the language of the particular policy. In that connection phrases such as “the larger settlement rule” and “the reasonably related rule” require to be used with care.

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council specifically ruled that the factors outlined in Knepper & Bailey were not relevant to the issue of allocation of defence costs, but the court suggested that they could be valid considerations in the context of allocation of settlement amounts. The latter point was argued on the appeal in Clearly Canadian.

The relevant insuring agreement in the New Zealand policy provided coverage for “…all Loss…which such Officer has become legally obligated to pay on account of any claim(s) made against him…for a Wrongful Act.” “Loss” was defined to include “the total amount of the Defence Costs”.

The Committee noted that there was no dispute that the costs relating wholly and exclusively to the defence of the insured defendant would be covered. Similarly there was no dispute that costs related wholly and exclusively to defence of non-insured defendants would not be covered. The real issue was over “those costs which relate both to his defence and to the defence of some other defendant or defendants.”

In the result, the Committee held that a proper construction of the policy allowed to be covered any cost “reasonably related” to the officer concerned. It held further that “reasonable relation” was a question of fact. The court noted that the “reasonably related rule” seemed to provide “a good shorthand way of indicating that all costs related to the officer are to be covered by the policy whether or not they are costs which also relate to another defendant whose costs are not covered, even though that other defendant may thereby be benefited.”

While a detailed discussion of the issue does not lend itself easily to the confines of a paper such as this, it is interesting to consider the argument that in D & O allocation disputes such as these, the bulk of the liability burden is not truly concurrent, since the bulk of the liability can be said to be the “direct” liability of the corporation, and not just “derivative” to the liability of the D & O’s. On this interpretation, “direct” liability can be seen as that liability that is created when the conduct of the D & O’s is deemed to be the act of the corporation (such as in the case of U.S. securities legislation). In such cases, it is arguably significant that the corporation would bear liability even if the D & O’s were not named as parties to the lawsuit. (And notably, conduct and liability of the corporation (“direct” liability) is not insured under a standard D & O policy.) In contrast, “derivative” liability is that resulting to the corporation only as a result of operation of law, e.g., respondeat superior.

One could make out an argument that in the case of “direct” liability, there should be apportionment, much like in a joint tortfeasor case. The logic of this approach is evident if one considers the converse result: if on the other hand the D & O’s were to be held liable for the full burden of such “direct” liability, and if corporation had its own insurer, then the D & O insurer would bear the burden rather than the corporation’s own liability insurer – even if the cause of action could have survived without the D & O’s being sued! An anomalous result indeed.

Given that in the United States (as a result of the trilogy) the prevailing rule (absent clear language in the policy) has become that a D & O insurer will pay 100 % of the burden of any settlement unless (a) the settlement is paid in part on behalf of uninsured parties for whose acts the corporation is responsible, or, (b) the settlement was made larger by reason of claims which the corporation alone could be held liable, many insurers are inserting provisions into their policies to gain better control over allocation and to avoid the effect of the trilogy.

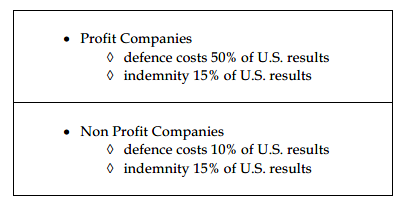

There is, however, a difference in approach, depending upon whether the insured is a “for profit” or “not-for-profit” entity.

In the case of “for profit” corporations, particularly public companies, traditionally these companies have not been able to obtain entity coverage. Insurers are only now, in response to the trilogy, offering entity coverage, and for securities claims only. Such coverage was originally extended by means of an endorsement; however, since 1996, it has been offered by many D & O insurers as part of their standard policy. Thus, in such cases, with both the D & O’s and the entity being covered, no issue of allocation arises in relation to securities claims.

In relation to non-securities claims, however, policies are being re-worded to stipulate allocation guidelines. For example, in its 5/95 form for D & O insurance, American Home has provided:

With respect to (i) Defense Costs jointly incurred by (ii) any joint settlement made by, and/or (iii) any adjudicated judgment of joint and several liability against the Company and any Director or Officer, in connection with any Claim other than a Securities Claim, the Company and the Director(s) and/or Officer(s) and the insurer agree to use their best efforts to determine a fair and proper allocation of the amounts as between the Company and the Director(s) or Officer(s) and the insurer, taking into account the relative legal and financial exposures of and the relative benefits obtained by the Directors and Officers and the Company. In the event that a determination as to the amount of the Defense Costs to be advanced under the policy cannot be agreed to, then the insurer shall advance such Defense Costs which the insurer states to be fair and proper until a different amount shall be agreed upon or determined pursuant to the provisions of this policy and applicable law. [emphasis added]

Such a provision should be clear enough to preclude any serious dispute over allocation.

In the case of “not-for-profit” corporations and organizations in Canada, the approach has in many ways been simpler. Many Canadian insurers have traditionally included entity coverage in their standard D & O cover for non-profit companies and organizations, perhaps recognizing that the non-profit corporation or organization may only act through its directors, and recognizing that most D & O’s do not receive any remuneration or compensation for serving as directors of a non-profit. Such coverage effectively shuts the door on allocation disputes.

III. STATUTORY REGULATION OF D & O POLICIES

While there are many Canadian statutes that affect the particular exposure of D & O’s and their need for specific coverage (this matter is discussed in the Section D, “Comparative Scope of Coverage”, below), it is critical for underwriters of Canadian D & O policies to understand the sources for the regulation and interpretation of D & O policies more generally.

It turns out that due to the fact that the provincial “uniform” Insurance Acts regulate by classification of policy type, and D & O policies do not fit into any of the types listed in the statute, D & O policies are (with some exceptions) largely regulated by the common law. For example, B.C.’s Insurance Act, which is based on the Anglo-Canadian provincial “uniform” Insurance Act, is divided into eight Parts:

Part 1 – Definitions, Interpretation and Application of Act;

Part 2 – General Provisions

Part 3 – Life Insurance

Part 4 – Accident and Sickness Insurance

Part 5 – Fire Insurance

Part 6 – Automobile Insurance

Part 7 – Miscellaneous Classes of Insurance

Part 8 – Administration

While the Insurance Act is stated to apply “…to every insurer that carries on any business of insurance in British Columbia and to every contract of insurance made or deemed to be made in British Columbia”, none of these Parts, except the general governing provisions (Parts 1 and 2), apply to D & O policies. Therefore, subject to that exception, D & O policies in Canada are regulated according to common law principles.

Some of the notable general governing provisions that apply to D & O policies are:

(a) a provision deeming certain contracts to be made in the province (which may impact upon the determination of the proper law of the contract);

(b) all terms and conditions of the policy must be set out in the policy or document in writing attached to it;

(c) provisions for relief against forfeiture;

(d) provisions regulating waiver of a term or condition;

(e) provisions concerning the limitation of legal actions;

(f) provisions regulating the furnishing of the application for insurance and policy wording; and

(g) provisions regarding the liability of a continuing insurer.

These provisions leave a great deal of latitude to the common law for the regulation of many issues. The cumbersome result is that for U.S. insurers wanting to learn about the applicable law on a given issue, finding answers is not as simple as referring to a statute for guidance. While comparable provisions in the Insurance Act(s) may provide some insight into how the common law is likely to treat these issues (given that the statutes often “codify” certain of the common law tests), nonetheless, for definitive answers, must be found in the case law.

One example of a common law test which has developed is the test for material disclosure by an insured. This issue is obviously a matter of critical importance to insurance underwriters, who depend on proper disclosure in making their underwriting decisions. For determining a non-disclosure problem, the common law test consists of determining whether the insured, at the application stage and during the policy period, made disclosure of all of the facts that a “reasonable D & O insurer” would consider material to the risk. The courts have made clear that a fact is material if it would cause a reasonable insurer to either decline the risk, or stipulate for a higher premium. However, what is reasonable is judged not by what the insurer believes to be reasonable but what the “general community” of D & O insurers would consider to be material to assessing the risk. There is no room for an underwriter with highly subjective or peculiar views as to what is material.

The theory which underlies the test is the notion that the insured knows everything about the risk and the underwriter knows virtually nothing; so, unless the insured makes full and complete and true disclosure, the underwriter cannot properly assess the risk.

At common law, the companion to this obligation being placed on an insured is, if the insured fails to make full and proper material disclosure, and the underwriter determines that there has not been disclosure of a material fact, then (provided the insurer acts quickly upon learning of the material non-disclosure), the insurer has the option to treat the policy as void and return the premium to the insured. In law, the effect is that there was never a policy and therefore the insurer need not respond to any claims.

However, an insurer is prohibited from “deeming” or classifying what is material to a policy. In every case, it is a question of fact for proper judicial authority. For example, the B.C. Insurance Act stipulates:

Misrepresentation and nondisclosure

13 (1) A contract is not rendered void or voidable by reason of any misrepresentation, or any failure to disclose on the part of an insured in the application or proposal for the insurance or otherwise, unless the misrepresentation or failure to disclose is material to the contract.

(2) The question of materiality is one of fact.

The exception to this, however, is that if an application for insurance includes a “basis” clause stipulating that the applicant warrants the information given and that it forms the basis for the application, this makes the answers to the questions on the application in the nature of a “true warranty”. In such cases, strict compliance with the terms of the warranty is required, and a breach of warranty does not have to be causative to void the policy from the date of the breach. The warranty effectively renders irrelevant whether the answers given are material, or the honesty and care given in answering the questions. If the answers given are untrue, the insurer is at liberty to rescind the policy (subject to its obligation to immediately return the premium).

There are many other common law principles applying to D & O policies in Canada. Under the circumstances, the best advice to underwriters is to seek legal advice as soon as possible on any issue that is not governed by the general statutory provisions.

IV. STATUS OF A D & O WHO IS AN “INNOCENT CO-INSURED”

One of the more interesting issues related to disclosure in the D & O context arises out of the fact that typically in Canada, an application for D & O insurance is signed by only one person and includes a “basis” clause as described above. The policy is stipulated to be based upon the “warranted” representations of the person who signs the application and those representations are deemed to be made on behalf of each D & O so as to bind all of them.

This raises the issue, “how does a misrepresentation, or material omission, by the signing party affect the other D & O’s insured under the policy?” This issue has been hotly contested in American D & O insurance law. Some guidance as to how Canadian courts may be expected to treat this situation in a D & O context can be found in the recent decision of the B.C. Court of Appeal in McKay v. Cowan.

The facts of the case involved a claims-made excess professional liability insurance policy issued to some lawyers, following an application made by only one of the lawyer insureds. The applicant lawyer failed to disclose his own ongoing fraudulent activities (dipping into a client’s account for a number of years); and when the police caught up with him, the insurer attempted to deny coverage to all of the insureds, even though there was no proof that the “innocent co-insureds” had either participated in, or had knowledge of, the culpable party’s fraudulent activities.

The insurer sought to deny coverage on the basis that the policy should be treated as void ab initio. The insurer relied to a large extent on the general rule in the law of agency that a principal is liable for the fraud of his agent acting in the scope of his employment and within the scope of his agency. The insurer also emphasized that the application form was in essence the foundation – almost a condition precedent – to the other insured’s coverage: had the culpable party not filled out the application, no policy would have been issued at all, whether for the benefit of the culpable party or anyone else.

The innocent insureds, on the other hand, argued strongly that the decision should be guided not by general rules of agency but rather, by the language of the policy, and what a reasonable person would expect regarding coverage, as a result of such language.

The relevant clauses in the policy read:

VIII. EXCLUSIONS

THIS POLICY DOES NOT APPLY:

(A) To any claim arising out of any act, omission or personal injury committed by the Insured with actual dishonest, fraudulent, criminal or malicious purpose or intent.

X. CONDITIONS

*****

I. WAIVER OF EXCLUSIONS AND BREACH OF CONDITIONS

Whenever coverage under any provision of this Policy would be excluded, suspended or lost:

(i) because of any dishonest, fraudulent, malicious or criminal act or omission by any Insured, or

(ii) because of non-compliance with any notice condition required solely because of the default or concealment of such default by one or more Insureds responsible for the loss or damages otherwise insured hereunder,

the Insurer agrees that such insurance as would otherwise be afforded under this policy shall continue in effect, cover and be paid with respect to each and every Insured who did not commit or personally participate in, or acquiesce in such activity and who did not remain passive after having personal knowledge of any act, omission or personal injury described in any such exclusion or condition; provided that if the condition be one with which the Insured can comply, the Insured entitled to the benefit of this Waiver of Exclusions and Breach of Conditions upon receiving such knowledge shall comply with such condition promptly after obtaining knowledge of the failure to of any other Insured to comply therewith.

…

L. MISREPRESENTATION

By acceptance of a Certificate hereunder each Insured agrees that the statements made in his application (if any) are true and the coverage provided to him by this policy shall be invalid if he has knowingly given false particulars or intentionally failed to disclose in his application any fact required to be stated.

The court accepted the innocent insureds’ argument that this provision was similar to a “severability clause” found in other policies. For example, the court noted that in the case of Shapiro v. American Home Assurance Co., the policy stated:

Except for the provisions of Condition (b) of this Insurance, this Insurance shall be construed as a separate contract with each Insured so that except as aforesaid, as to each Insured, the reference in this Insurance to the Insured shall be construed as referring only to that particular Insured, and the liability of the Insurer to such Insured shall be independent of its liability to any other Insured.

In the result, the court held that due to the waiver of exclusions clause, the insurer would have to provide coverage for the innocent co-insured and the insurer could not hold the “fraud exclusion” against them, unless the insurer could prove that the innocent co-insureds had themselves acted wrongfully in actual fact. In short, the court concluded that the wrongful conduct could not be imputed on the basis merely that other person applied for coverage.

The court commented:

Although this case involves a different kind of insurance from that considered in Panzera, so far as the rights of multiple insureds are concerned, I am unable to see any real distinction between the two. Here, [the innocent co-insureds] claim the benefit of an insurance policy issued upon the application of [the guilty insured]. In Panzera, the mortgagee claimed the benefit of an insurance contract issued upon the application of the property owner. In both cases the insurer contends that the misrepresentation of the applicant should be imputed to the those claiming the benefit of the insurance. In Panzera, that argument could not survive an interpretation of the contract language, in light of the reasonable expectations of the parties. Whether it can be sustained in this case ultimately depends on an interpretation of this contract’s provisions in the same manner. Panzera makes clear that the agency argument is displaced by contractual language and reasonable expectations of the parties to the contrary.

The court suggested that if there was a concern that the culpable party would be unjustly enriched, e.g. by a situation of the insurer paying all of the losses even though it was due to the wrongful act of the uninsured culpable party, the insurer could address the problem by inserting a subrogation clause into the policy to allow it to recover against the “breached” insured.

In rejecting the insurer’s argument on agency, the court underlined the insurer’s failures in preventing what happened:

Looked at from [the insurer’s] perspective, it agreed to issue a “claims made” policy providing coverage for claims falling within the policy definition, not only for the liability of the applicant [who at the time of the application was no longer associated in a firm with the other insureds], but for predecessor firms as well. It collected a premium for each of the lawyers named in the application (including [one but not the other of the innocent co-insureds]), and it required the signature of only one person as “owner or partner”. It did not require a personal declaration concerning anticipated claims from every lawyer or firm from which insured claims might arise, and it did not contract on the basis that only the applicant was to be insured. In terms of control over the consequences of misrepresentation in the application, [the insurer] was in a better position than either [of the innocent co-insureds]. [The insurer] had the means to protect itself either in the way it chose to issue the coverage, or by the choice of language in the policy.

It seems more realistic, in these circumstances, to resolve disputes over the rights of multiple insureds under the contract on the basis of the language the insurer chose to employ in the policy, than to impute wrongdoing to an innocent insured on the basis of a notional and wholly artificial “agency”.

Such an approach is also more in accord with the realities of modern law practice. Modern law firms frequently comprise dozens, sometimes hundreds, of lawyers. Some are partners, some are employees. The members of the firm in both categories change from time to time, as partners and associates leave or retire, new partners are created, and new associates are employed. The only practical means of insuring against liability, in these circumstances, is for one application to be made by a responsible member of the firm, acting on behalf of all the others. If insurers could deny coverage to hundreds of Canadian lawyers insured in this way, because of misrepresentation of the individual who filled out the application on their behalf, the consequences to the public and tot he profession would be enormous, quite unanticipated, and entirely inconsistent with the practical realities faced by the legal profession and the insurance industry.

While the latter comments were obviously directed to the particular context of insuring a law firm, and the insurer’s failure to take appropriate precautions to protect its interests under the circumstances, the comments raise an interesting question as to whether a court would be inclined to come to a similar conclusion, or impose a similar burden upon an insurer in circumstances of a corporate D & O setting. It is submitted that while much would depend upon the particular circumstances at issue, it is likely that for a large company with many D & O’s, the same result could be anticipated.

It is also important to remember that absent the presence of a “Waiver of Exclusions” provision in the policy, an insurer would be entitled to raise a properly worded exclusion in defence of a claim by even an innocent co-insured, or for the purposes of voiding the policy on grounds of a material misrepresentation in the application for insurance. Such an exclusion clause should be worded as “…any claim arising out of any act, omission or conduct committed by an Insured with actual dishonest, fraudulent, criminal or malicious purpose or intent…” Notably, if the exclusion were worded as “the Insured”, an innocent insured could successfully argue that the exclusion only applied to claims made by the particular insured whose conduct was actually in issue.

The approach outlined in McKay was adapted from similar approaches in other contexts. In coming to its conclusion, the court drew from prior consideration of the issue of an “innocent co-insured”, in the context of fire insurance fraud and in the context of an innocent mortgagee affected by the fraud of a mortgagor in relation to insurance flowing from a standard mortgage clause in a fire insurance policy.

V. COMPARATIVE SCOPE OF COVERAGE

Earlier in this paper, we introduced very briefly the unique statutory and common law framework which applies to the regulation of D & O policies in Canada, from a “regulation of insurance policies” perspective.

However, two more introductions are crucial to rounding out the picture of D & O insurance law in Canada:

1. A brief overview of some statistics on claims patterns in Canada; and

2. A discussion of the different sources (both common law and statutory) for D & O liability in Canada.

Each of these will be discussed in the context of D & O’s acting for both “for profit” companies and “non-profit” organizations.

1. Some brief statistics on claims patterns

The following is a brief outline of the source for claims in Canada:

| Source | Percent of Total Claims |

| Customers and suppliers | 60% |

| Shareholders | 3% |

| Employees | 14% |

The “severity” of claims is as follows:

In terms of the frequency of claims by industry type: (most frequent to less frequent):

| Type of Risk | Ratio |

| Natural resources | 0.19 |

| Financial services | 0.16 |

| Wholesale and retail | 0.12 |

| Insureds with U.S. subsidiaries | 0.35 |

| With no U.S. subsidiaries | 0.10 |

Looking at the statistics from a general perspective, it is evident that Canadian society, as a whole, favours the regulatory route, as opposed to civil litigation. Another general explanation for the comparatively low incidence of lawsuits is the fact that in Canada, the loser is responsible to pay the other party’s legal costs. Finally, Canadian law affords significant substantive protection to D & Os that act within the scope of their authority, absent any fraud.

2. Sources of liability for D & O’s in Canada

(a) Common Law Duties

The leading Canadian decision to outline the duties of a director is Canadian Aero Service v. O’Malley. There it is said that a director’s duties are the “duties of loyalty, good faith, avoidance of conflict of interest between duty and interest and avoidance of personal profit”.

Such duties apply to directors, whether they serve on the board of a “for profit” company or a “non-profit” organization.

The standard of care for a director is generally to meet “the standard or skill of a reasonably prudent person in similar circumstances”.

In the case of directors of charities, the standard in Canada may be raised even higher. In certain cases, directors of charities may be held to the standard of a trustee and required to meet that “which a reasonable and prudent person would adopt in the management of that person’s own affairs.”

While the standard of care for directors of charities has not been finally determined in every Canadian province, applying the standard of trustee seems to be the trend in Ontario. The court’s comments in the case of Re Public Trustee and Toronto Humane Society, an Ontario case concerning a society recognized as a “charitable organization”, highlight the court’s overriding concern to protect the interests of the charitable donors to the organization. The court stated:

The position on the one hand is that the corporation is the trustee of its property, and that since the corporation is without body to be kicked or soul to be damned, its directors must be held to the duties and obligations of trustees. On the other hand is the argument that the corporation is a corporation duly regulated by statute and that, as long as the provisions of the statute are appropriately observed, the obligations of the directors have been met.

…

Whether one calls them trustee in the pure sense (and it would be a blessing if for a moment one could get away from the problems of terminology), the directors are undoubtedly under a fiduciary obligation to the Society and the Society is dealing with funds solicited or otherwise obtained from the public for charitable purposes…There is no trust document, and I have already indicated that I do not consider the ordinary corporate safeguards to be adequate…I realize that it is common practice for commercial corporations to pay directors, as directors, and often as officers of a corporation, as well. The Society is not a commercial corporation nor is it simply a son-profit corporation; it is a charitable institution.

The court concluded that the society at issue was “…answerable in certain respects for its activities and the disposition of its property as though it were a trustee…”.

(b) Statutory Sources

As one might expect, there is a long list of “unique-to-Canada” exposures which flow from Canadian federal or provincial statutes affecting and creating D & O responsibilities and liabilities. While it is not possible within the scope of this paper to address each of the general areas of exposure in any lengthy detail, below we identify the significant statutes and areas of concern for insurers to take steps to “Canadianize” their D & O programs. A selection of sample policies is attached as Appendix “A” to the paper.

The Competition Act

The Competition Act is federal legislation that was adopted in Canada in 1985. It creates a “level playing field” so that business in Canada remains competitive. The Act is enforced by the Ottawa-based Competition Bureau.

While the Act grants numerous powers to the Competition Bureau to take action against improper conduct, and creates a number of criminal law offences, it also provides for a statutory civil cause of action52 for damages in favour of a party suffering loss or damage as a result of prohibited conduct or failure to comply with an order of the Tribunal or a court. Both the company and/or its directors and officers may be sued, either together or alone. As in U.S. securities legislation, liability for directors and officers can arise even where the company is not liable. Typical plaintiffs under the Act are customers and competitors.

The kinds of misconduct that can create a D & O exposure under the Act include:

(a) conspiracy or combining to limit facilities, manufacturing of a product, or preventing or lessening competition in the production or supply, etc. of a product or service;

(b) bid-rigging;

(c) conspiracy relating to reducing opportunities for professional sport players;

(d) agreements or arrangements among financial institutions to fix interest rates or charges;

(e) illegal trade practices (including discriminatory pricing, lessening competition or selling at unreasonably low prices to eliminate a competitor);

(f) exclusive dealing, tied selling and market restrictions;

(g) misleading advertising;

(h) publishing scientific data that is not sufficiently proven;

(i) double ticketing retail products;

(j) pyramid selling;

(k) bait and switch selling;

(l) abuse of dominant market position;

(m) price fixing and maintenance; and

(n) not selling at an advertised price.

Claims under the Competition Act are increasing in Canada more rapidly than securities claims. Without a special endorsement, certain of the claims would potentially not be covered under a typical D & O policy. While those claims which resemble a regular negligence suit would likely be covered, certain types of conduct within the purview of the Act would not necessarily be covered, because of the following typical “dishonesty” exclusion found in a standard D & O policy:

The insurer shall not be liable to make any payment for Loss in connection with a Claim made against an Insured:

…arising out of, based upon or attributable to the committing in fact of any criminal or deliberate fraudulent act.

It should be noted that the endorsements which are being written for Competition Act claims afford both D & O and entity coverage. This obviates the need for any concern over allocation.

Insurers that are explicitly affording Competition Act coverage are not covering applications in respect of knowing contempt, such as a failure to testify or a failure to produce records.

Limits of liability remain the same, despite the additional coverage provided for in the endorsement.

“Oppression” and “Unfairly Prejudicial Conduct” Liability

The concept of minority shareholder rights, as provided for in U.S. legislation, is largely unknown to Canadian law. In Canada, however, the federal Canada Business Corporations Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-44 and the provincial Business Corporations Acts (or equivalents) protect minority shareholders in ways not available in the United States. All federal and provincial statutes empower minority shareholders to apply to a court for an order on the ground that the affairs of the company are being conducted, or the powers of the directors are being exercised, in a manner oppressive to a shareholder of the company, or unduly prejudicial to such applicant shareholder. Such provisions were patterned on English legislation developed following World War II.

Because of the broad and equitable nature of the “oppression” and “unfairly prejudicial” provisions in the legislation, minority shareholders are choosing increasingly to frame their complaints under these statutory provisions. The provisions are worded broadly enough to encompass a variety of complaints which might otherwise be difficult to categorize in any uniform way. Such provisions are particularly being relied upon in respect of complaints of “freezing out” of a minority, and “watering down” of shareholder rights.

The statute provides that as a remedy, the court may:

(a) direct or prohibit any act or cancel or vary any transition or resolution;

(b) regulate the conduct of the company’s affairs in future;

(c) provide for the purchase of the shares of any member of he company by another member of the company, or by the company;

(d) in the case of a purchase by the company, reduce the company’s capital or otherwise;

(e) appoint receiver or receiver manager;

(f) order that the company be wound up under part 9;

(g) authorize or direct that proceedings be commenced in the name of the company against any party on the terms the court directs;

(h) require the company to compensate an aggrieved person; and

(i) direct the rectification of any record of the company.

Insurers that are providing coverage for this kind of risk are specifying coverage for claims related to:

(a) the improper sale of option shares by D & O’s (to raise capital) where shareholders had pre-emptive rights;

(b) compensation for a shareholder that has been locked out from the company;

(c) compensation in respect of watering down of shares by the issuance of new classes of shares; and/or

(d) squeezing out under the Company Act provisions.

Some common exclusions include:

(a) non-monetary claims, such as a claim for an injunction.

(b) directors who are also shareholders

(c) claims by an insured (D & O) against the company or the company against an insured (the “insured versus insured” exclusion)

“Statutory” Liability

Other liabilities that D & O’s may be exposed to in the Canadian context are “statutory” claims arising from a failure to comply with the provisions of the federal Income Tax Act, R.S.C. 1985 (5th Supp.), the Excise Tax Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. E-15, provincial sales tax legislation, the Unemployment Insurance Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. U-1, the Canada Pension Plan Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 8, the Canada Business Corporations Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-44, the Ontario Business Corporations Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. B-16 and counterpart provincial legislation, and section 251.18 of the Canada Labour Code (which deals with D & O liability for unpaid wages in respect of employees working in inter-provincial undertakings in the Yukon or Northwest Territories not otherwise regulated by federal or provincial legislation).

Failures under these statutes generally can be summarized as a failure by the directors and officers to ensure that the corporation deduct, withhold or remit:

(a) tax;

(b) unemployment insurance contributions; or

(c) pension plan contributions; or

(d) a failure to pay wages owing to employees.

By imposing personal liability upon directors, the legislation places a significant burden of “due diligence” upon directors.

In general, such statutory liability for wages and taxes applies to directors and officers, whether they are serving in a profit or non-profit context. The only exception that exists is if the director is serving on the board of a charity. In certain instances which do vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, directors may be exempted from personal liability for wages.

The statutes impose a direct statutory joint and several liability upon the directors and officers, more so than as provided in similar U.S. legislation. They also provide a remedial power to the governments to collect damages without recourse to civil litigation. Liability can potentially be significant: for example, in the case of employee wages, under both the Ontario and the federal Business Corporations Act, the statutes provide for personal liability in respect of debts owing for a period of six months’ wages. Liability for excise taxes also has the potential to be severe: the federal Goods and Services Tax, for example, provides for a 7% levy on goods and services; and most provinces charge a further levy. As a result of the personal exposure, many directors are resigning when a company approaches insolvency, rather than being faced with the exposure.

A related topic is statutory liability under retirement benefits legislation. Claims could be brought against D & O’s for breach of responsibilities, obligations or duties imposed upon fiduciaries by the Canada Pension Benefits Standards Act, 1985, R.S.C. 1985, c. 32 (2nd Supp.), or the Ontario Pension Benefits Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P.8, the Canada Labour Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. L-2, the Labour Adjustments Benefits Act, S.C. 1996, c. 23 or any federal or provincial workers compensation or any similar statutory or regulatory law.

Endorsements covering these types of liabilities generally provide coverage only for the D & O’s personal liability and not entity coverage for the company. Endorsements typically include a subrogation clause, allowing the insurer to subrogate against the company for such payments out to the directors and officers.

When designing a “statutory” liability endorsement, one problem that needs to be addressed adequately is ensuring that the policy does not appear inconsistent in including “taxes” under the standard “losses that are not covered” clause, then stipulating coverage for tax liabilities in the endorsement. As in other cases, policies need to be reviewed carefully for a consistent approach.

“Pollution” Liability

The liability here is federal and provincial statutes which have been enacted in the past decade which provide for personal liability of D & O’s by reason of any environmental harm. The statutes at issue are the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, the Ontario Environmental Protection Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. E-19, the British Columbia Environmental Management Act, and other provincial counterpart laws. The statutes feature the development of site registries and mandatory disclosure requirements in respect of environmental harm.

The environmental harm in issue is “the release into the environment of a toxic substance”, as those terms are defined, by a person who owns the substance, has charge of it or causes or contributes to its release. The liability is associated with failing to take steps to prevent such release or, if the release cannot be prevented, failing to take such reasonable steps to remedy the dangerous condition or to reduce or mitigate any threat to the environment or to human life or health.

Statutes in some of the jurisdictions provide a statutory cause of action against the directors and officers, whether or not the company is sued.

The D & O insurance coverage which is contemplated addresses economic loss only, covering for example, a claim against the D & Os in respect of a drop in share prices due to the announcement of a pollution liability, a claim in respect of loss of goodwill to the company as a result of a problem with government authorities in respect of an environmental hazard, or a claim in respect of a loss in ability to obtain lenders or new investment for the company.

A typical exclusion clause highlights what is not covered:

This policy does not provide coverage for claims…

(a) arising out of, based upon or attributable to the committing in fact of any statute, rule, regulation, agreement, or judicial or regulatory order or other final adjudication adverse to the Insured which establishes such a purposeful violation, or impeding, preventing or attempting to impede, any inquiry or examination under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, R.S.C. 1985, . 16 (4th Supp.), the regulations promulgated thereunder and amendments thereto;

(b) for property damage including, inter alia, asbestos or asbestos-containing materials, or acid rain conditions;

(c) for any direction or request to test for, monitor, clean up, remove, contain, treat, detoxify or neutralize Pollutants

Because of the exclusions above, if an insured wants coverage for property damage, bodily injury or clean-up costs, they will require more specialized environmental coverage for such purposes.

Because the legislation is so new, it is difficult to predict at this juncture the frequency and severity of claims.

From an underwriting perspective, some of the key questions to ask are:

(a) whether the applicant has written policies and procedures in place for the handling, transportation, or disposal of hazardous substances or waste, or for raising environmental issues and concerns;

(b) particulars about an “environmental policy”, if one exists;

(c) whether there is a corporate officer assigned to overview environmental issues and compliance with environmental regulations;

(d) whether the applicant uses an environmental consultant firm to advise it;

(e) details re: policies and procedures re: public disclosure of environmental incidents and/or hazards;

(f) whether waste haulers that are used are licensed to transport hazardous waste and substances;

(g) whether assets and acquisitions are regularly evaluated for their potential pollution exposure;

(h) details re planned corporate acquisitions or mergers;

(i) whether any director or officer has knowledge of any claims or acts, errors, omissions or conduct that may lead to claims under the proposed endorsement.

Dispute Resolution Clauses

While dispute resolution clauses are fairly standard in American D & O policies and commonly refer to prevailing legislation, with few exceptions, there is no legal requirement to submit to alternative dispute resolution (ADR) in Canada. The process is entirely consensual.

From an underwriting standpoint, an appropriate wording that would achieve a comparable routing of disputes to ADR would be:

In the event of a dispute or difference which may arise under or in connection with this policy, whether arising before or after termination of this policy, either party may elect to have any such dispute or difference submitted to an alternative dispute resolution process (“ADR”) as set forth herein.

Either the Insurer or the Insureds may elect the type of ADR discussed below; provided, however, that the Insureds shall have the right to reject the Insurer’s choice of ADR at any time prior to its commencement, in which case the Insureds’ choice of ADR shall control.

The Insurer and Insureds agree that there shall be two choices of ADR: (1) non-binding mediation in which the Insurer and the Insureds shall try in good faith to settle the dispute by mediation under or in accordance with its then-prevailing Canadian Mediation Rules; or (2) arbitration conducted under and in accordance with the Ontario Arbitration Act, 1991, S.O. 1991, c. 17. In either mediation or arbitration, the mediator(s) or arbitrators shall have knowledge of the legal, corporate management, or insurance issues relevant to the matters in dispute. The mediator(s) or arbitrators shall also give due consideration tot he general principles of the law of the state where the Named Entity is incorporated or formed in the construction or interpretation of the provisions of this policy; provided, however, that the terms, conditions, provisions and exclusions of this policy are to be construed in an even-handed fashion in the manner most consistent with the relevant terms, conditions, provisions or exclusions of the policy. In the event of arbitration, the decision of the arbitrators shall be final and binding and provided to both parties. In the event of mediation, either party shall have the right to commence a judicial proceeding; provided, however, that no such judicial proceeding shall be commenced until the mediation shall have been terminated and at least 120 days have elapsed from the date of the termination of the mediation. In all events, each party shall share equally the expenses of the ADR.

The “Duty to Defend” Endorsement

While a duty to defend clause is certainly not standard in American D & O coverage, it is more common in Canada. Such a clause grants the insurer the right and duty to defend any claim covered by the policy, even if the allegations are false, groundless, or fraudulent. It also has the advantage of giving the insurer more control over defence costs, which are usually covered.

The insurer’s liability and obligations cease upon exhaustion of the limits of liability, so the endorsement cannot be said to broaden coverage.

Subject to the inclusion of entity coverage, allocation of defence costs will remain an issue as between the insured D & O’s and the non-insured corporation.

Concepts which may not be transferable: Bre-X and “fraud on the market” doctrine

D & O litigation is growing in Canada and lawyers are in many instances looking to the judicial experience in the United States for ideas with which to build arguments for and against liability. The chances are, the issue has been litigated before in the United States, and often, the cases are so voluminous that it is possible to find an authority for just about any proposition!

However, inasmuch as Canadian courts often do follow an American “lead” on an issue, this is not always the case. It is important to remember that concepts that may be taken for granted in the United States may be wholly inapplicable in the Canadian legal context.

One such concept is the “fraud on the market” theory, which has been widely accepted in U.S. securities litigation, since 1988. The theory permits certain assumptions to be made about the securities market, and in effect, reduces the need for claimants in a securities fraud case to prove all of the usual elements of securities fraud.

Specifically, to state a “normal” case of securities fraud in the U.S. under Rule 10b-5, the following elements must be alleged:

A. a misleading statement or omitted statement;

B. materiality of the misstatement;

C. scienter on the part of the person doing the misleading;

D. reliance by the plaintiff on the misstatement or omission;

E. damages suffered by the plaintiff as a result;

F. a causal link between the damages suffered and the material misstatement or omission.

However, where a plaintiff sues relying on the “fraud on the market” theory, the plaintiff need not specifically prove each of the foregoing elements. This because, as explained by Judge Walker in the U.S. proceedings in Re Clearly Canadian Securities Litigation:

…A securities market fraud case proceeds on the assumption that investors rely on the integrity of the market to establish a fair and correct price for openly traded securities. Hence, there is no need to prove that individual investors relied on any particular information about the prospects of the security’s issuer. Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 244-47, 108 S Ct. 978, 990-91, 99 L. Ed. 2d 194 (1988); In re Seagate Technology II Sec. Litig., 843 F. Supp. 1341, 1355 (N.D. Cal. 1994). Moreover, an allegation that the defendants’ misstatement distorted the market price of the security itself satisfies three of the elements required to state a claim for fraud (i.e. elements B, E, F). See Jonathan R. Macey, Geoffrey P. Miller, Mark L. Mitchell & Jeffrey N. Netter, Lessons from Financial Economics: Materiality, Reliance, and Extending the Reach of Basic v. Levinson, 77 Va. L. Rev. 1017 (1991). Given the presumption of reliance, when an alleged misstatement or omission occurs (element A) and affects the trading price of the security on the open market, this price effect denotes the materiality of the misinformation put into the market, satisfying element (B). The price effect, it is theorized, also furnishes elements (E) and (F). Because defendants misled the market, the market, according to the theory, was unable correctly to value the security, whose price diverged from its true value, leading plaintiffs to overpay for (or in the rare case undersell) the security, causing plaintiffs’ damages. The amount of those damages is simply the amount of the divergence. See Green v. Occidental Petroleum Corp., 541 F 2d 1335, 1341-42 (9th Cir. 1976) (Sneed, J., concurring).

Acceptance by the court of the “fraud on the market” theory therefore effectively obviates the need for a plaintiff to plead every element of a securities fraud. The plea is reduced to two essential elements: (A) and (C) above, together with an allegation that the price of the security responded significantly to the alleged misstatement or omission.

This simplification of the elements of the cause of action gives U.S. plaintiffs an advantage, in that whereas the material misstatement or omission and its effect on the price will be obvious to the plaintiff from the outset of pleading, elements such as the particulars (who said (or failed to say) exactly what, and when), may be unknown at the time of pleading.

In Canada, by way of contrast, under certain provincial regulatory securities legislation (which varies from province to province), a statutory civil cause of action for misrepresentation or fraud in relation to a prospectus and/or press release generally requires proof of:

(a) a misrepresentation in a prospectus, circular or notice; and

(b) damages resulting from such misrepresentation.

Potential defendants include: the issuer or seller of the security, the underwriter of the security, every director of the issuer at the time the prospectus or amendment to the prospectus was filed, every person whose consent was filed, and every person who signed the prospectus.

The right of action is for either an action for damages or a right of rescission.

Interestingly, if a misrepresentation in a prospectus or circular is proven, reliance by the purchaser upon such misrepresentation is deemed, where the misrepresentation was in the prospectus at the time of purchase. Also, the amount recoverable by a claimant is capped at “the price at which the securities were offered to the public”, and a defendant is not liable for “all or any portion of such damages that the defendant proves do not represent the depreciation in value of the security as a result of the misrepresentation.”

There are various defences available to the defendants to show that they had no knowledge of the misrepresentation, or in good faith reasonably relied on expert opinion in making such misrepresentation, without knowledge of the misrepresentation, or to say that the plaintiff was aware of the misrepresentation at the time of purchase. Some statutes provide simply that there is no liability where the act or omission was done or omitted to be done in compliance with the Act, or, any requirement, order or direction pursuant to the Act.

In most provinces, there is no provision for assuming that the market has priced the stock or security in reliance upon the corporate representations.

Interestingly, section 196 of the Quebec Securities Act makes the likelihood of an effect on the market price a condition of the offences there listed. Section 196 provides:

196. Every person is guilty of an offence who makes a misrepresentation that is likely to affect the value or the market price of a security in any of the following documents:

1) the different kinds of prospectuses or the offering notice provided for in Title II;

2) the information presented in the annual report and incorporated in the simplified prospectus;

3) the information in respect of a reporting issuer provided for in paragraph 1 of section 85;

4) the information document provided for in section 67;

5) the annual, semi-annual or quarterly financial statements provided for in Title III;

6) the press release provided for in Title III;

7) the circular prepared in connection with a solicitation of proxies in accordance with Title III;

8) the take-over bid circular and issuer bid circular provided for in Title IV.

Section 197 of Quebec’s Securities Act clarifies that making a misrepresentation other than one that affects the price may also be an offence:

197. Every person is guilty of an offence who in any manner not specified in section 196 makes misrepresentation

1) in respect of a transaction in a security;

2) in the course of soliciting proxies or sending a circular to security holders;

3) in the course of a take-over bid, a take-over bid by way of an exchange of securities or an issuer bid;

4) in any document or information filed with the Commission or one of its agents;

5) in any document forwarded or record kept by any person pursuant to this Act.

However, Title VIII, Chapter II of Quebec’s Securities Act providing for a civil right of civil for damages does not limit the right of action in respect of a misrepresentation to only those misrepresentations that “are likely to affect the price”.

As already discussed supra, Canada’s federal Competition Act also creates a civil cause of action for loss and damages resulting from a breach of that Act’s provisions. In each case, the breach and its causal connection to the loss must be established, for the cause of action to succeed.

Such statutory remedies supplement but do not replace any civil remedies available at law. Apart from the statutory causes of action, there are the common law causes of action for negligent and fraudulent misrepresentation, which have a more general purview than the statutory remedies. The common law cause of action for fraud in Canada consists of proving that a representation was:

(a) made knowingly, or

(b) without belief in its truth, or

(c) recklessly, without caring whether it was true or false.

The same test applies to fraudulent omissions. Whether an action is for negligent or fraudulent misrepresentation, detrimental reliance must be proven by the claimant in an action for damages in each case.

In a recent interlocutory decision out of the Ontario Court (General Division) in the high profile intended class action proceeding styled Carom et al. v. Bre-X Minerals Ltd. et al., the court was asked to consider the applicability of the U.S. “fraud on the market” theory to Canada. This ongoing suit involves proceedings by shareholders and others against the D & O’s of the famous (and infamous) mining exploration company, Bre-X Minerals Ltd., and against various promoter securities houses and stock analysts employed by the brokerage firms. The stock, which loomed to fame and brought fortune to many as a result of its rise from meagre $0.50 beginnings to prices of $228, fell in value to nothing, following revelations that the gold samples had been “salted”.

In an October, 1998 application to court, the representative plaintiffs sought amendments to add to their Statement of Claim facts relying on the American “fraud on the market” theory. Application of the doctrine to Canada was previously untested in Canadian courts.

The request to make the amendments was refused. Notably, the test for allowing amendments to pleadings is that generally, such amendments are to be granted, unless there is prejudice which cannot be compensated by costs or an adjournment. Furthermore, such an amendment should only be refused where the amendment would result in another proceeding to strike it out as being “plain and obvious” that it discloses no reasonable cause of action. The court’s refusal to allow the amendment was therefore a strong refusal by the court to open the door to the doctrine being applied in Canada.

The court’s reasons in the Bre-X application provide a good example of the differences in the U.S. and Canadian approach to a securities action, and are worthwhile examining for that reason.

As observed by the court, the Plaintiffs’ pleadings in the Bre-X action were replete with common law allegations of negligent misrepresentation and fraudulent misrepresentation (in addition to pleas of statutory liability). As we have noted, in Canadian law, a key component of these common law causes of action is that the Plaintiff must prove “detrimental reliance” on the negligent or fraudulent statement in each case.

After a review of the American doctrine, the court stated, “Effectively, the fraud on the market theory creates a rebuttable presumption of reliance on certain misrepresentations, thus obviating the need to prove such reliance on an individual basis.”

The plaintiffs proposed to amend the pleadings to say that the market price of the shares represented misrepresentations disseminated by the defendants; and that therefore, the purchase or holding of such shares by the plaintiffs or the defendant promoters constituted proof of reliance on each and every statement made by the defendants. Obviously, if the theory were accepted, it would make proof of reliance on the alleged misrepresentations easier.